LONDON: During excavations at the ancient site of Abydos in Egypt in 2009, archaeologists made an unexpected discovery – the remains of a lost Coptic monastery, probably founded in the 5th century by the leader of the Coptic Church, Apa Moses.

This was already fascinating enough, but even greater surprises were yet to come.

Deep within the excavated ruins of the monastery, archaeologists from Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities made a discovery that shed light on the tensions that existed between the early Coptic Church and the remnants of Egypt’s “pagan” past.

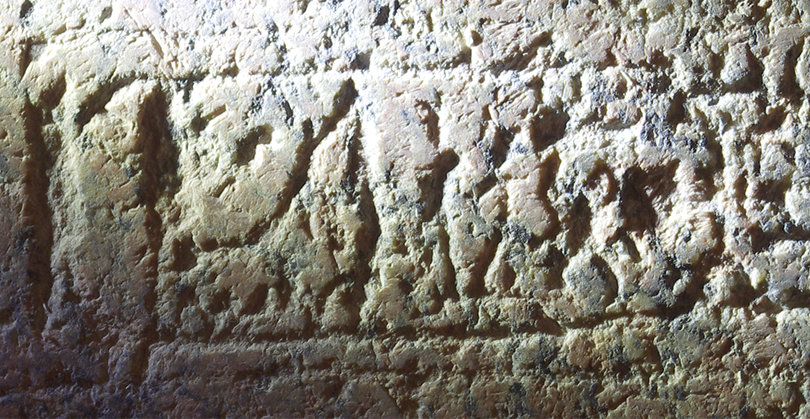

A piece of red granite, 1.7 metres long and half as wide, was brought into use as a modest threshold for the monastery.

Merneptah’s sarcophagus. (Photo courtesy: Frédéric Payraudeau)

A partial inscription revealed that it was part of the sarcophagus of Menkheperre, high priest of Amun-Ra, the ancient Egyptian god of the sun and air who ruled southern Egypt from 1045–992 BC

The find seemed to solve one mystery – where Menkheperre was buried. Previously, it was thought that he must have been buried near his power base in Thebes, in a tomb that had not yet been discovered. Now it seemed that he was buried in Abydos.

The existence of a fragment of his sarcophagus, placed in the floor of the monastery, as the authors of the work published in 2016 suppose, is to some extent the result of “the persecution of local pagan temples” by Apa Moses and was “perhaps the result of the zeal with which his followers demolished pagan buildings and Tombs at Abydos.

And this is where the whole story could have ended, if not for Frederic Payraudeau, an Egyptologist from the Sorbonne in Paris.

Frederic Payraudeau, Egyptologist from the Sorbonne University in Paris. (Delivered)

Ayman Damrani and Kevin Cahail, the Egyptian and American archaeologists who discovered the fragment, noted from the beginning that the sarcophagus had another occupant before Menkheperre.

They noticed that the earlier inscriptions had been overwritten and suggested that the original owner may have been an unknown prince.

They wrote that the fragment, made of hard red granite, required “a significantly greater investment of time and resources in its construction” than would be devoted to the sarcophagus of even a high official.

This suggests that the original owner “had access to royal-level workshops and materials” and may have been, they deduced, a prince named Meryamunre or Meryamun.

“When I read this article, I was very interested because I am a specialist in this period,” Payraudeau said, “and I was not entirely convinced when I read the inscriptions.”

He added: “I already suspected that this fragment came from the king’s sarcophagus, partly because of the quality of the object, which is very well carved, but also because of the decorations.”

They included scenes from the Book of Gates, an ancient Egyptian funerary text reserved almost exclusively for kings.

“It is known in the Valley of the Kings on the walls of tombs and on the sarcophagi of kings, and in the later period it was used only by one person who was not a king.

“But that’s an exception, and it would be very strange for a prince to use that line – especially a prince we haven’t heard of.”

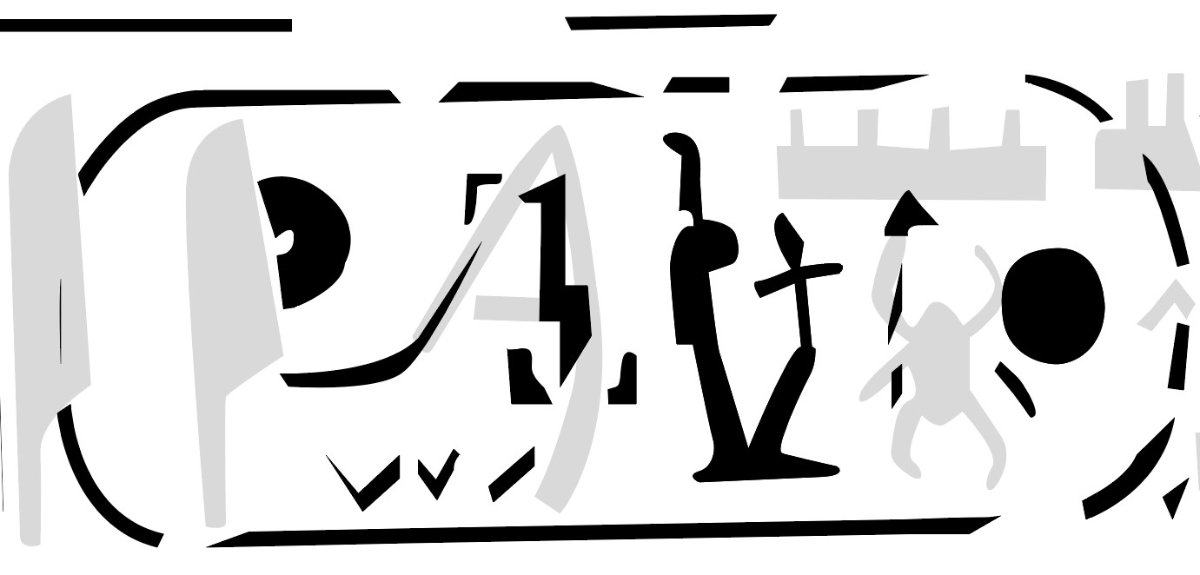

The photos published with the newspaper were too low quality to confirm his suspicions, so he asked the author to send him a high-resolution copy. “And when I saw the enlarged photographs of the objects, I could clearly see the king’s cartouche.”

Royal cartouche, i.e. an inscription containing the name of Ramesses. (Photo courtesy: Frédéric Payraudeau)

The cartouche is an oval frame, highlighted at one end and containing a name in hieroglyphs, used to designate the royal family. This one read: “User-Maat-Ra Setep-en-Ra.”

Translated roughly as “The Justice of Ra is Mighty, the Chosen of Ra”, it was the throne name of one of the most famous rulers of ancient Egypt – Ramesses II.

Ramesses II, who ruled from 1279 to 1213 BC, is considered one of the most powerful warrior pharaohs of ancient Egypt, famous for fighting many battles and creating many temples, monuments and cities. He was known to generations of subsequent rulers and their subjects as the “great ancestor”.

The royal cartouche, or inscription, containing the name of Ramesses (Photo courtesy: Frédéric Payraudeau)

His reign was the longest in Egyptian history. Images of him can be found on over 300 statues, often colossal, found throughout the ancient kingdom.

After his death, after a reign of 67 years, he was buried in a tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Because many of his tombs were later plundered, one of his successors, Ramesses IX, who ruled from 1129 to 1111 BC, had many of his remains moved for safekeeping to a secret tomb at Deir El-Bahari, a necropolis on the Nile opposite the city of Luxor.

They lay there undisturbed for almost 3,000 years until their accidental discovery by a goatherd around 1860.

It wasn’t until 1881 that Egyptologists learned of the extraordinary find. Among the more than 50 pharaonic mummies, each with detailed information about who they were and where they were originally buried, was Ramesses II.

He lay in a beautifully carved cedar wood coffin. It was originally placed in a golden coffin – lost in ancient times – which in turn was placed in an alabaster sarcophagus, which was then placed in a stone sarcophagus.

Small fragments of an alabaster sarcophagus, which was probably destroyed by robbers, were found in his original tomb in the Valley of the Kings. But there was no trace of the granite sarcophagus — until now.

Grave robbing and the reuse of sarcophagi were a result of social and economic upheavals in ancient Egypt. “A sarcophagus was meant to be used by its owner for eternity,” Payraudeau said.

However, with the death of Ramesses XI in 1077 BC, at the end of a long period of prosperity, there was civil war and then a long period of unrest, he added.

“This was the Third Intermediate Period, during which there was a lot of looting of necropolises, because the Egyptians knew that the tombs contained gold, silver, and other valuable materials, such as wood.”

In addition to the usual grave robbers, even the authorities took part in the looting, processing sarcophagi for their own use. Menkheperre was thus buried in the sarcophagus previously used by Ramesses II.

Payraudeau is not convinced that using a fragment of a sarcophagus during the construction of a fifth-century Coptic monastery was necessarily an act of disrespect.

“When they built this monastery, they didn’t know they were reusing Ramesses’ sarcophagus because by then no one had been able to read hieroglyphs for about 500 years.”

The year was 1799 before the Rosetta Stone was discovered, which, by royal decree written in three languages, including ancient Greek, provided the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphic writing.

The only mystery that currently remains, Payraudeau said, is where in Abydos Menkheperre was originally buried.

“There must be undiscovered remains of the high priest’s tomb somewhere,” he said.

“It may have been completely destroyed. But I can’t help but think that perhaps parts of the sarcophagus that were suitable for pavements etc. were reused, and that the lid, which would be much more difficult to reuse, could still lie intact somewhere in Abydos.”

In 1817, some 3,000 years after the death of Ramesses II, archaeological discoveries in Egypt inspired the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley to write a sonnet reflecting on how the once seemingly eternal power of the great king, known to the ancient Greeks as Ozymandias, had turned to dust.

Reflecting on the inscription on the pedestal of a broken, fallen statue, a fragment of the poem reads: “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings. Look upon my works, you mighty ones, and despair! Nothing remains but the decay of this colossal wreck. Boundless and barren, lonely and level, the sands stretch far away.

In fact, not only has Ramesses II’s fame increased in the 3,236 years since he was buried in the Valley of the Kings, but he also became the most traveled of the ancient pharaohs.

In 1976, when it was noticed that his mummified remains were beginning to decompose, Ramesses was sent to the Musee de l’Homme in Paris for restoration, along with a whimsical “passport” that listed his occupation as “King (deceased)”.

Since then it has been seen by hundreds of thousands of visitors at numerous exhibitions around the world, including on a return visit to Paris last year.

If the lid of his sarcophagus were discovered, it could be reunited with his mummy and coffin, and the depiction of Ozymandias would undoubtedly gain in popularity, further undermining Shelley’s poetic prophecy that the Great Ancestor would be forgotten and swallowed by the sands of time.